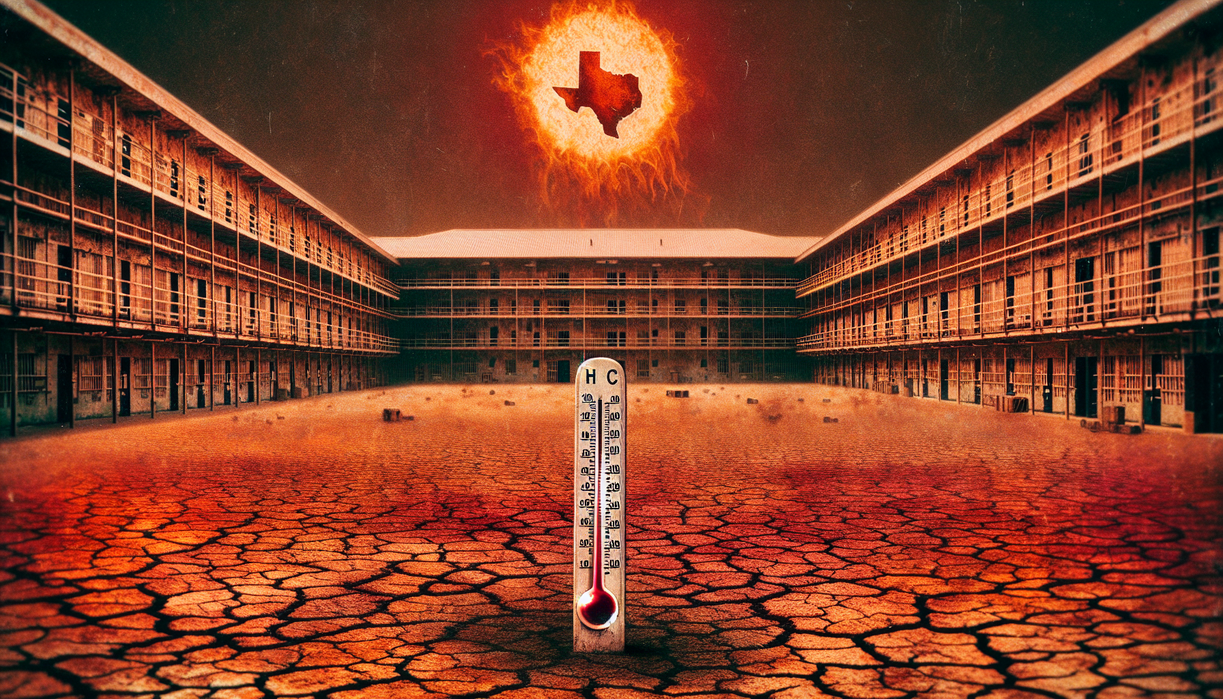

www.twilightpoison.com – When we talk about punishment, context often gets lost. Nowhere is that clearer than inside Texas prisons, where summer heat regularly pushes indoor temperatures past 90 degrees, sometimes much higher. In any other correctional context, those numbers would likely violate basic standards, yet for thousands of incarcerated people, this has become a seasonal routine rather than an emergency.

Texas officials are about to defend that reality in court, arguing that the current conditions fit within legal and operational context. Their stance collides with a growing body of data, expert opinion, and lived experience suggesting that extreme heat transforms a prison sentence into something harsher than what any judge ordered. The outcome of this legal fight will reshape how we think about accountability, safety, and responsibility in the broader context of mass incarceration.

Texas Heat in Context: Numbers Behind the Bars

New analysis of state records offers a troubling context for just how hot Texas prisons become each summer. Many housing units, especially those without air conditioning, record temperatures well above 90 degrees for extended periods. In some facilities, readings approach or exceed triple digits during peak afternoon hours. In the context of occupational health, similar conditions at a factory or construction site would likely trigger mandatory protections, cooling breaks, or even shutdowns.

Yet inside these prisons, the heat does not simply pass after a brief surge. It lingers through long, humid nights, turning concrete and metal into heat sinks. People sleep on thin mattresses that hold warmth, next to walls that radiate stored heat back into small cells. In this context, the body has fewer chances to cool down, raising the risk of heat exhaustion, dehydration, or worse. Even those with no preexisting conditions feel their energy drain, while vulnerable residents face life-threatening stress.

State officials often emphasize budget constraints and aging facilities to explain this context. They highlight efforts like adding fans, providing ice water, and adjusting schedules. These steps matter but fail to change the core reality: in many units, the daily context remains one of sustained, oppressive heat. When policies for county jails or juvenile facilities require stricter temperature limits, it sharpens the question of why state prisons operate under a very different standard in the same geographic and climatic context.

Legal Context: When Heat Becomes a Constitutional Question

The looming courtroom battle will unfold inside a complex legal context shaped by the Eighth Amendment, which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment. Courts have previously found that extreme heat in prisons can violate constitutional rights, especially for those with medical vulnerabilities. In that context, temperatures are not just a comfort issue; they become part of the punishment itself. Advocates argue that Texas has long known about these risks yet moved too slowly or too narrowly to address them.

State attorneys, on the other hand, lean heavily on institutional context. They may point out that many southern states operate prisons without full air conditioning, that budgets are finite, and that retrofitting old buildings would cost hundreds of millions of dollars. They also emphasize security concerns, insisting that any major infrastructure overhaul must account for staffing, movement, and surveillance. In this narrative, heat becomes one factor among many in a tough operational context rather than a standalone constitutional crisis.

My own perspective is that law cannot be interpreted in a vacuum, stripped of real-world context. When a government confines people, it assumes responsibility for their basic safety. That does not mean prisons must be comfortable resorts. It does mean conditions should not push human bodies beyond what they can reasonably tolerate, especially for days or weeks at a time. If comparable contexts—other secured facilities, including some jails and federal prisons—are required to maintain safer temperatures, then Texas must justify why its context should remain an exception, not the rule.

Human Context: Lived Reality Behind the Data

Numbers alone cannot capture the daily context of living through a Texas summer in a sealed unit. Former prisoners often describe wet towels wrapped around their heads, makeshift fans fashioned from folded cardboard, and the constant search for shade in spaces with little ventilation. People with heart disease, asthma, or mental health conditions experience symptoms intensify as the heat climbs. Medication can impair the body’s ability to regulate temperature, placing some at even higher risk. Staff live in this context too, sweating through long shifts, trying to balance custody duties with basic compassion. From my view, the most honest assessment emerges when we place medical science, legal standards, and these lived narratives side by side. That fuller context reveals a simple truth: extreme heat is not a background inconvenience. It is a central feature of the punishment structure in Texas prisons, one that was never explicitly debated in a courtroom or legislative chamber, yet now sits at the heart of this legal reckoning. The question for Texas, and for all of us observing, is whether we accept that reality or decide that context demands change. A reflective look at our values suggests we should not wait for another heat wave, another lawsuit, or another avoidable death before acting.