www.twilightpoison.com – The story of Western Colorado University’s new Bird Friendly Campus status only makes sense when we zoom out to the wider content context of bird life across North America. A landmark study released in 2019 estimated nearly three billion birds have vanished since 1970, roughly a 30% decline. When you walk across a campus lawn or past a dorm courtyard today, the morning chorus often feels thinner. Fewer songs, fewer silhouettes on power lines, more silence tucked between buildings.

Seen through this content context of long‑term loss, Western’s designation becomes more than a nice sustainability badge. It signals a cultural shift, a recognition that even modest urban and campus spaces can offer critical habitat. Grass strips, native shrubs, student gardens, storm‑water ponds, glass façades, every small piece of the built environment shapes daily survival odds for local birds. A campus can either add to the problem or help reverse the trend.

Understanding the content context of bird decline

To grasp why the Bird Friendly Campus label matters, you first need the content context behind those haunting numbers. The 2019 study did not simply count fewer birds at a few feeders. Researchers used decades of data from radar, breeding surveys, and migration counts. When combined, the evidence drew a blunt conclusion: common species are shrinking in abundance, not only rare or already threatened ones. Sparrows, blackbirds, warblers, swallows, familiar companions of fields and neighborhoods, all show steep drops.

Many people react with disbelief because the decline hides inside everyday routine. You still see pigeons downtown, geese on athletic fields, jays yelling from tall trees. Yet this visible slice of bird life can mask deeper shifts. Imagine a stadium where three out of ten seats suddenly go empty, permanently. The game still continues, but the energy changes. That quieter, thinner quality mirrors what has happened across skies and backyards over the past fifty years.

Several forces drive this loss, each woven into the broad content context of modern life. Habitat conversion removes nesting spaces and food. Reflective glass and bright night lighting turn campuses into hazards along migration routes. Domestic cats kill staggering numbers of birds. Pesticides thin insect populations, starving aerial insectivores. Climate shifts gradually rearrange seasons and resources, creating subtle mismatches between birds and their food. The result looks like death by many small cuts rather than a single dramatic wound.

How Western’s campus fits into the larger story

Western Colorado University sits at an intriguing intersection of human infrastructure and wild landscape. Nestled near the Rockies, the campus lies on pathways used by migrants moving between breeding grounds and winter ranges. It also supports resident species that rely on trees, shrubs, and grassy corners throughout the year. From this perspective, the campus becomes part of a living corridor rather than an isolated academic island. The content context of each building, lawn, and plaza influences how easily birds can rest, feed, and move.

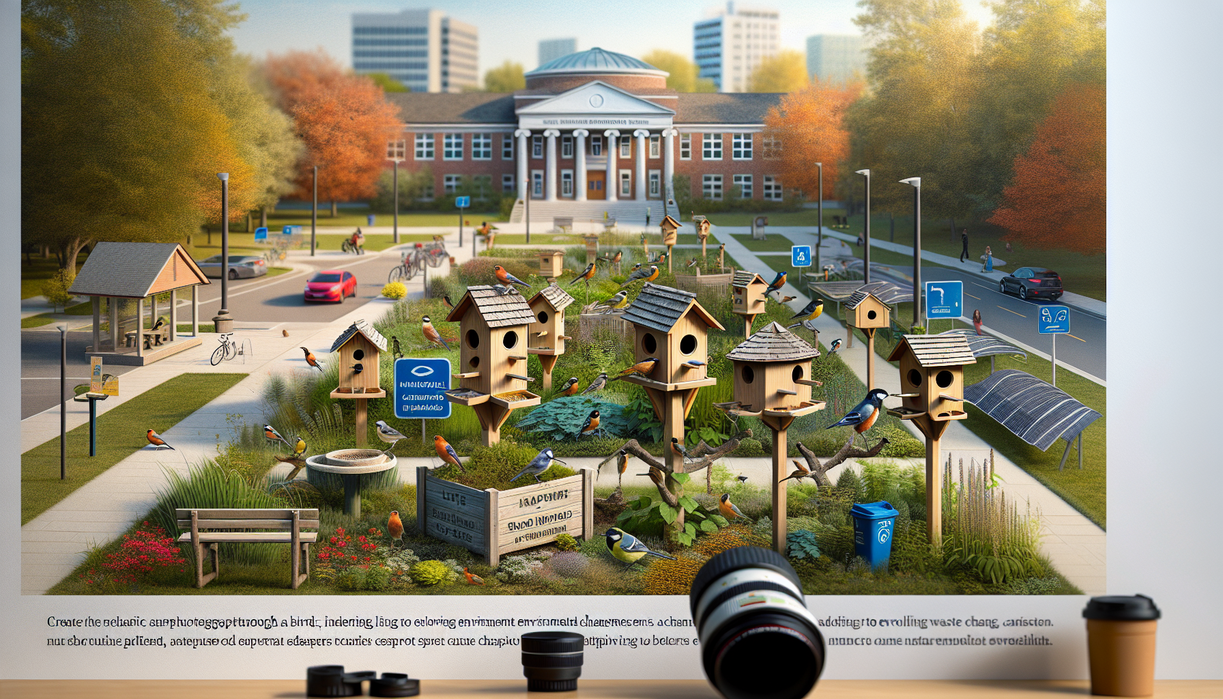

The Bird Friendly Campus recognition usually reflects multiple efforts that address those quiet pressures. Windows may receive patterned film or dot grids to cut collisions. Landscape plans often favor native vegetation, which supports richer insect life and provides better shelter. Mowers can leave selected areas taller or even convert them into meadows, reducing disturbance. Lights might be dimmed or redirected during peak migration. Policies may encourage students to keep cats indoors. None of these steps alone solves the problem, yet together they reshape the local content context from hazard to refuge.

I see Western’s status as both achievement and invitation. It celebrates current progress while also challenging students, faculty, and neighbors to keep asking, “What else can we do?” The designation becomes a living commitment rather than a static award. Every dorm renovation, new parking lot, or outdoor classroom offers another chance to strengthen this bird‑supportive content context. The campus turns into a lab where people can test solutions, measure impact, and share results with other institutions.

Small actions, big impact: a personal take

For me, the most powerful part of Western’s Bird Friendly Campus story lies in its reminder that even modest efforts carry real weight when viewed through the wider content context of bird decline. A decal on a window, a darkened dorm room during migration, a student choosing native plants for a club garden, each gesture seems trivial on its own. Yet multiplied across thousands of campuses, offices, suburbs, and farms, those choices add up. We often wait for sweeping policy shifts, while overlooking the influence of our own built spaces. Western’s example shows how an institution can weave care for birds into daily design decisions, research projects, and campus culture. It nudges all of us to treat every courtyard, balcony, and office window as a tiny piece of a continental safety net for birds, then act accordingly. The future of birdlife depends not only on remote wilderness, but also on how thoughtfully we inhabit the places we already call home.